Proposed MLB-Cuba Deal Spells Trouble for U.S. Hopefuls

by Joe Guzzardi

ML--argues that, among the agreement's other advantages, Cuban players would no longer have to defect which often involved being smuggled or trafficked into countries from which they could then reach the U.S.

Since the Department of Justice recently announced a sweeping probe of MLB's international signing practices and widespread corruption throughout the $10 billion industry, the league's deal with Cuba may have been coordinated to deflect criticism. According to documents Sports Illustrated obtained, a 2015 chart created by Los Angeles Dodgers' executives ranking its Latin American employees on an "egregious" behavior scale. The Dodgers ranked 15 employees on a five-point scale ranging from a one, "mostly just an innocent bystander," to a five that's equated with "criminal" behavior. Five Dodgers' employees received a five.

Rumors of MLB's tacit support of trafficking Cubans have been intensifying since 2014 when the Dodgers' Yasiel Puig came to the team via the Mexican drug cartel Los Zetas who kidnapped the outfielder, and held him hostage. Eventually, Puig signed a seven-year contract for $42 million.

In the last five years, at least 20 Cuban nationals have signed ML--contracts for an aggregate $300 million. Another ugly smuggling story: the Chicago White Sox Jose Abreu confessed to a Miami grand jury that while in transit to Florida where he knew federal immigration agencies were waiting, he ate as much of his fake U.S. passport as he could swallow to cover up his illegal travel, and to ensure his eventual $68 million contract.

Adding Cubans to ML--rosters is a mixed bag of success and failure. After tolerating Puig's on- and off-the-field antics that included an arrest for driving 110 MPH in a 70-MPH zone, the Dodgers traded him to the Cincinnati Reds. And although Abreu has performed well, the White Sox have finished fourth in a five-team league in each of his five seasons.

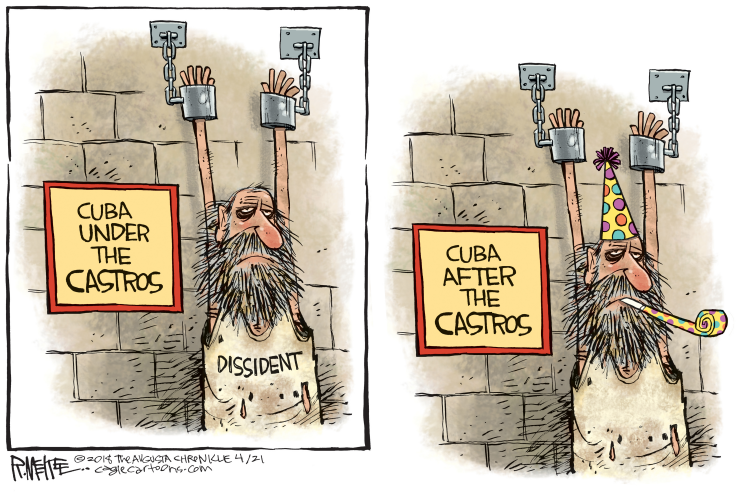

Beyond the dubious practice of going into business with the virulently anti-American RaC:l Castro regime to negotiate the future of young Cuban baseball chattel, another major fallout from any agreement, assuming the Trump administration approves it, is its effect on American players. Expanding the international baseball pool that already includes players from the Dominican Republic, Venezuela and several Asian countries makes it more difficult for Americans to break in.

Playing baseball is a job, and at that, the world's best job, some would argue. The starting salary is about $550,000 annually, the average salary is nearly $4.38 million, and superstars earn more than $30 million. Players belong to the nation's strongest union, and teams cater to players' whims. ML--is handing foreign nationals jackpots, while qualified U.S. kids are passed over. University of Texas' legendary manager Augie Garrido said that despite their considerable skill, the majority of college players never play organized baseball after they graduate.

An educated guess: if the 2018 College World Series champion Oregon State Beavers wore ML--uniforms, the average fan would accept them as highly qualified, and would enjoy the game just as much as they do watching pros. CWS players are fundamentally sounder baseball-wise, and - better yet - don't have to be illegally trafficked.

Welcome to corporate America's 21st century business model. Whether the employer is Silicon Valley-headquartered or one of the 30 ML--franchises, employers' reflexive instinct when good jobs become available is to go abroad even though a wealth of local talent is available.

-

Joe Guzzardi is a Progressives for Immigration Reform analyst who has written about immigration for more than 30 years. Contact him at [email protected].